Your Prostate

The prostate is both an accessory gland of the male reproductive system and a muscle-driven mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation. It is found in all male mammals. It differs between species anatomically, chemically, and physiologically. Anatomically, the prostate is found below the bladder, with the urethra passing through it. It is surrounded by an elastic, fibromuscular capsule and contains glandular tissue, as well as connective tissue.

The prostate glands produce and contain fluid that forms part of semen, the substance emitted during ejaculation as part of the male sexual response. This prostatic fluid is slightly alkaline, milky or white in appearance. The alkalinity of semen helps neutralize the acidity of the vaginal tract, prolonging the lifespan of sperm. The prostatic fluid is expelled in the first part of ejaculate, together with most of the sperm, because of the action of smooth muscle tissue within the prostate. In comparison with the few spermatozoa expelled together with mainly seminal vesicular fluid, those in prostatic fluid have better motility, longer survival, and better protection of genetic material.

Disorders of the prostate include enlargement, inflammation, infection, and cancer. The word prostate comes from Ancient Greek προστάτης, prostátēs, meaning "one who stands before", "protector", "guardian", with the term originally used to describe the seminal vesicles.

Structure

The prostate is a gland of the male reproductive system. In adults, it is about the size of a walnut and has an average weight of about 11 grams, usually ranging between 7 and 16 grams. The prostate is located in the pelvis. It sits below the urinary bladder and surrounds the urethra. The part of the urethra passing through it is called the prostatic urethra, which joins with the two ejaculatory ducts. The prostate is covered in a surface called the prostatic capsule or prostatic fascia.

Blood and lymphatic vessels

The prostate receives blood through the inferior vesical artery, internal pudendal artery, and middle rectal arteries. These vessels enter the prostate on its outer posterior surface where it meets the bladder, and travel forward to the apex of the prostate. Both the inferior vesical and the middle rectal arteries often arise together directly from the internal iliac arteries. On entering the bladder, the inferior vesical artery splits into a urethral branch, supplying the urethral prostate; and a capsular branch, which travels around the capsule and has smaller branches which perforate into the prostate.

The veins of the prostate form a network – the prostatic venous plexus, primarily around its front and outer surface. This network also receives blood from the deep dorsal vein of the penis and is connected via branches to the vesical plexus and internal pudendal veins. Veins drain into the vesical and then internal iliac veins.

The lymphatic drainage of the prostate depends on the positioning of the area. Vessels surrounding the vas deferens, some of the vessels in the seminal vesicle, and a vessel from the posterior surface of the prostate drain into the external iliac lymph nodes. Some of the seminal vesicle vessels, prostatic vessels, and vessels from the anterior prostate drain into internal iliac lymph nodes. Vessels of the prostate itself also drain into the obturator and sacral lymph nodes.

Genes

About 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and almost 75% of these genes are expressed in the normal prostate. About 150 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the prostate, with about 20 genes being highly prostate specific. The corresponding specific proteins are expressed in the glandular and secretory cells of the prostatic gland and have functions that are important for the characteristics of semen, including prostate-specific proteins, such as the prostate specific antigen (PSA), and the Prostatic acid phosphatase.

Prostate’s Function

In ejaculation

In ejaculation, the prostate secretes fluid which becomes part of semen. Semen is the fluid emitted (ejaculated) by males during the sexual response. When sperm are emitted, they are transmitted from the vas deferens into the male urethra via the ejaculatory duct, which lies within the prostate gland. Ejaculation is the expulsion of semen from the urethra. Semen is moved into the urethra following contractions of the smooth muscle of the vas deferens and seminal vesicles, following stimulation, primarily of the glans penis. Stimulation sends nerve signals via the internal pudendal nerves to the upper lumbar spine; the nerve signals causing contraction act via the hypogastric nerves. After traveling into the urethra, the seminal fluid is ejaculated by contraction of the bulbocavernosus muscle. The secretions of the prostate include proteolytic enzymes, prostatic acid phosphatase, fibrinolysin, zinc, and prostate-specific antigen. Together with the secretions from the seminal vesicles, these form the major fluid part of semen.

In Urination

In urination the prostate's changes of shape, which facilitate the mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation, are mainly driven by the two longitudinal muscle systems running along the prostatic urethra. These are the urethral dilator (musculus dilatator urethrae) on the urethra's front side, which contracts during urination and thereby shortens and tilts the prostate in its vertical dimension thus widening the prostatic section of the urethral tube, and the muscle switching the urethra into the ejaculatory state (musculus ejaculatorius) on its backside.

In case of an operation, e.g. because of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), damaging or sparing of these two muscle systems varies considerably depending on the choice of operation type and details of the procedure of the chosen technique. The effects on postoperational urination and ejaculation vary correspondingly.

Problems

Inflammation

Prostatitis is inflammation of the prostate gland. It can be caused by infection with bacteria, or other noninfective causes. Inflammation of the prostate can cause painful urination or ejaculation, groin pain, difficulty passing urine, or constitutional symptoms such as fever or tiredness. When inflamed, the prostate becomes enlarged and is tender when touched during digital rectal examination. The bacteria responsible for the infection may be detected by a urine culture.

Acute prostatitis and chronic bacterial prostatitis are treated with antibiotics. Chronic non-bacterial prostatitis, or male chronic pelvic pain syndrome is treated by a large variety of modalities including the medications alpha blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories and amitriptyline, antihistamines, and other anxiolytics. Other treatments that are not medications may include physical therapy, psychotherapy, nerve modulators, and surgery. More recently, a combination of trigger point and psychological therapy has proved effective for category III prostatitis as well.

Enlarged Prostate

An enlarged prostate is called prostatomegaly, with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) being the most common cause. BPH refers to an enlargement of the prostate due to an increase in the number of cells that make up the prostate (hyperplasia) from a cause that is not a malignancy. It is very common in older men. It is often diagnosed when the prostate has enlarged to the point where urination becomes difficult. Symptoms include needing to urinate often (urinary frequency) or taking a while to get started (urinary hesitancy). If the prostate grows too large, it may constrict the urethra and impede the flow of urine, making urination painful and difficult, or in extreme cases completely impossible, causing urinary retention. Over time, chronic retention may cause the bladder to become larger and cause a backflow of urine into the kidneys (hydronephrosis).

BPH can be treated with medication, a minimally invasive procedure or, in extreme cases, surgery that removes the prostate. In general, treatment often begins with an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist medication such as tamsulosin, which reduces the tone of the smooth muscle found in the urethra that passes through the prostate, making it easier for urine to pass through.[ For people with persistent symptoms, procedures may be considered. The surgery most often used in such cases is transurethral resection of the prostate, in which an instrument is inserted through the urethra to remove prostate tissue that is pressing against the upper part of the urethra and restricting the flow of urine. Minimally invasive procedures include transurethral needle ablation of the prostate and transurethral microwave thermotherapy. These outpatient procedures may be followed by the insertion of a temporary stent, to allow normal voluntary urination, without exacerbating irritative symptoms.

Cancer

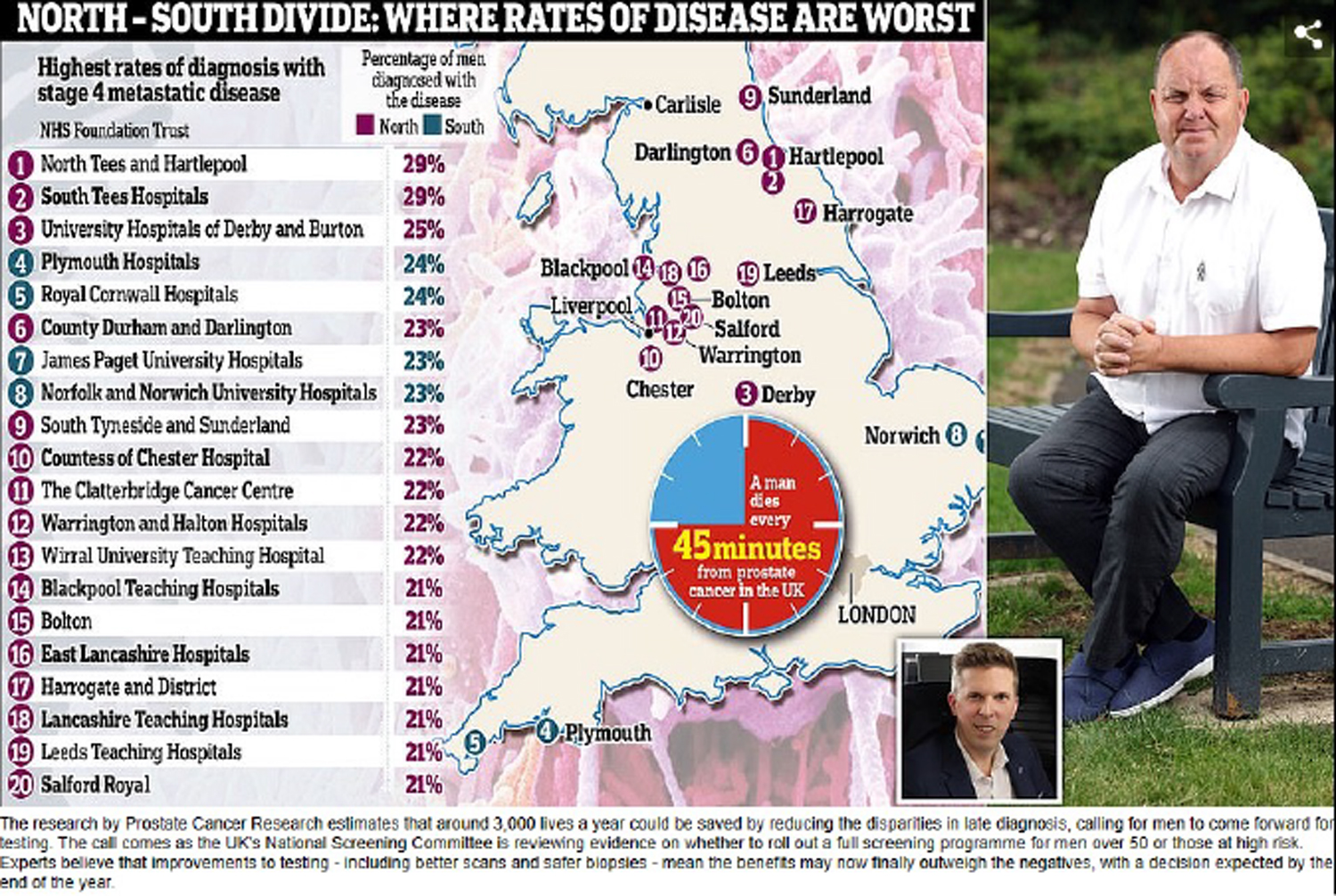

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers affecting older men in the UK, US, Northern Europe and Australia, and a significant cause of death for elderly men worldwide. Often, a person does not have symptoms; when they do occur, symptoms may include urinary frequency, urgency, hesitation and other symptoms associated with BPH. Uncommonly, such cancers may cause weight loss, retention of urine, or symptoms such as back pain due to metastatic lesions that have spread outside of the prostate.

A digital rectal examination and the measurement of a prostate-specific antigen level are usually the first investigations done to check for prostate cancer. PSA values are difficult to interpret, because a high value might be present in a person without cancer, and a low value can be present in someone with cancer. The next form of testing is often the taking of a prostate biopsy to assess for tumour activity and invasiveness. Because of the significant risk of overdiagnosis with widespread screening in the general population, prostate cancer screening is controversial. If a tumour is confirmed, medical imaging such as an MRI or bone scan may be done to check for the presence of tumour metastases in other parts of the body.

Prostate cancer that is only present in the prostate is often treated with either surgical removal of the prostate or with radiotherapy or by the insertion of small radioactive particles of iodine-125 or palladium-103, called brachytherapy. Cancer that has spread to other parts of the body is usually treated also with hormone therapy, to deprive a tumour of sex hormones (androgens) that stimulate proliferation. This is often done through the use of GnRH analogues or agents (such as bicalutamide) that block the receptors that androgens act on; occasionally, surgical removal of the testes may be done instead. Cancer that does not respond to hormonal treatment, or that progresses after treatment, might be treated with chemotherapy such as docetaxel. Radiotherapy may also be used to help with pain associated with bony lesions.

Sometimes, the decision may be made not to treat prostate cancer. If a cancer is small and localised, the decision may be made to monitor for cancer activity at intervals ("active surveillance") and defer treatment. If a person, because of frailty or other medical conditions or reasons, has a life expectancy less than ten years, then the impacts of treatment may outweigh any perceived benefits.

Surgery

Surgery to remove the prostate is called prostatectomy, and is usually done as a treatment for cancer limited to the prostate, or prostatic enlargement. When it is done, it may be done as open surgery or as laparoscopic (keyhole) surgery. These are done under general anaesthetic. Usually the procedure for cancer is a radical prostatectomy, which means that the seminal vesicles are removed and vas deferens is also tied off. Part of the prostate can also be removed from within the urethra, called transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). Open surgery may involve a cut that is made in the perineum, or via an approach that involves a cut down the midline from the belly button to the pubic bone. Open surgery may be preferred if there is a suspicion that lymph nodes are involved and they need to be removed or biopsied during a procedure. A perineal approach will not involve lymph node removal and may result in less pain and a faster recovery following an operation. A TURP procedure uses a tube inserted into the urethra via the penis and some form of heat, electricity or laser to remove prostate tissue.

The whole prostate can be removed. Complications that might develop because of surgery include urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction because of damage to nerves during the operation, particularly if a cancer is very close to nerves. Ejaculation of semen will not occur during orgasm if the vas deferens are tied off and seminal vesicles removed, such as during a radical prosatectomy. This will mean a man becomes infertile. Sometimes, orgasm may not be able to occur or may be painful. The penis length may change if the part of the urethra within the prostate is also removed. General complications due to surgery can also develop, such as infections, bleeding, inadvertent damage to nearby organs or within the abdomen, and the formation of blood clots.

History

The prostate was first formally identified by Venetian anatomist Niccolò Massa in Anatomiae libri introductorius (Introduction to Anatomy) 1536 and illustrated by Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius in Tabulae anatomicae sex (six anatomical tables) in 1538. Massa described it as a "glandular flesh upon which rests the neck of the bladder," and Vesalius as a "glandular body". The first time a word similar to 'prostate' was used to describe the gland is credited to André du Laurens in 1600, who described it as a term already in use by anatomists at the time. The term was however used at least as early as 1549 by French surgeon Ambroise Pare.

Prostate cancer was first described in a speech to the Medical and Chiurgical Society of London in 1853 by surgeon John Adams and increasingly described by the late 19th century. Prostate cancer was initially considered a rare disease, probably because of shorter life expectancies and poorer detection methods in the 19th century. The first treatments of prostate cancer were surgeries to relieve urinary obstruction. Samuel David Gross has been credited with the first mention of a prostatectomy, as "too absurd to be seriously entertained" The first removal for prostate cancer (radical perineal prostatectomy) was first performed in 1904 by Hugh H. Young at Johns Hopkins Hospital; partial removal of the gland was conducted by Theodore Billroth in 1867.

Prostate Health: What You Should be Checking for Every Decade.

King Charles has made public the fact that he is undergoing a procedure for an enlarged prostate, to encourage more men to get theirs checked. So, what are the warning signs men should be looking out for and how does this change as they get older? Here are the symptoms to know about, depending on your age group.

30s

Prostate cancer is strongly related to age and is very rare in young men. Around the world, however, there has been an increase in early onset prostate cancer in men between 15 and 40 years old. While it is not yet known why this rise has occurred, it is thought the type of prostate cancer you get when you’re younger may be different from prostate cancer with a later onset. If you get a prostate cancer diagnosis when you’re younger, it’s more likely to be in a more advanced stage and five-year survival rates are lower.

Ashwin Sridhar, consultant urologist at the Princess Grace Hospital (part of HCA UK), specialises in treatment of prostate and bladder conditions. He says: “Prostate cancer is extremely rare in men under 40 and there is nothing you can do prophylactically to reduce risks, however keeping healthy with a good diet and exercise may help. There is also a relationship between smoking and prostate cancer but it’s not definite that smokers will get it.”

40s

Generally, the 40s are still a safe zone, however certain groups may be at higher risk at this time of life, as Dr Sridhar explains: “There are three factors that increase risk — one is age and another is ethnicity. Men from Afro-Caribbean backgrounds tend to be at higher risk and if they do develop prostate cancer it tends to be more aggressive. The third risk factor is having a first-degree relative who has had the disease, such as a father or brother. If this applies to you, you have twice the risk compared with the general population. If more than one direct relative has had the disease, the risk is five times more than the general population. If you have a family history, we suggest talking to a doctor about having a PSA [prostate specific antigen] blood test in the first instance, as this test screens for prostate cancer.”

50s

Men in their 50s who have no risk factors should pay attention to their waterworks as from this decade onwards, rates of prostate cancer begin to rise. From 40 to 49, rates in the UK are around 20 per 100,000; from 50 to 54, rates increase to 1,737 per 100,000; and from 55 to 59 it jumps to 4,160 per 100,000. At this age, men should look for signs such as trouble urinating, disrupted flow of urine and trouble emptying the bladder. It is also a good age to start pelvic floor exercises, as Dr Sridhar explains: “If you do get diagnosed, having a good pelvic floor and being generally fit will help if you need treatment.”

60s

Continue to look for possible symptoms. These could include difficulty starting to urinate or emptying your bladder, a weak flow when you urinate, a feeling that your bladder hasn’t emptied properly, dribbling urine after you finish urinating, needing to urinate more often than usual (especially at night) and a sudden need to urinate. You may sometimes leak urine before you get to the toilet. If you are concerned, speak to a GP, and request a screening PSA test.

70s

Rates in the UK peak between the ages of 70 and 74, with an average of 11,153 cases recorded per 100,000 males per year between 2016 and 2018. It remains important to stay fit and healthy. Many men with prostate cancer do not experience symptoms until the disease has spread. This means that they risk being diagnosed too late when the cancer is incurable. If it spreads to other parts of the body, symptoms could include back pain, hip pain or pelvic pain, problems getting or keeping an erection, blood in the urine or semen and unexplained weight loss.

80s

“By the age of 80 and above, 60 to 70 per cent of men will have prostate cancer,” says Dr Sridhar. “At this age, the cancer is not very active, and most patients will live with it as it is unlikely to affect lifespan.”

Source The Telegraph